A Bull in a China Shop: Dennis Rodman and Finding Solace in Fashion

Graphic by Isabelle Hauf-Pisoni.

CW: Mentions of Suicide

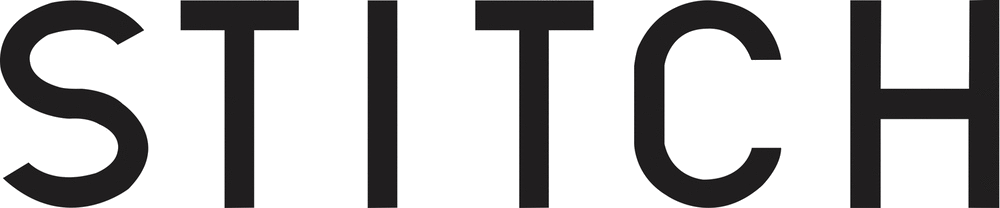

Rodman starring alongside Jean-Claude Van Damme in “Double Team" (1997). Image courtesy of Getty Images.

Menacing. Monstrous. Perfectly polished turquoise fingernails. Pest. Unmanageable. Pink boas and nightly neon hair dye. Aggressor. Freak. One of a kind.

Dennis Keith Rodman, housing insecure airport janitor turned Hall of Fame NBA defender turned ubiquitous Hollywood delinquent, was also an iconoclast of lingering ‘90s conventionality. Through his frequent “antics” on and off the court, he transpired a persona of unabashed self-expression that transcended rigid interpretations of black masculinity.

Rodman started almost too humbly: an impoverished 5’11'' high school graduate who was more than lacking on the court. But a few years and a nine-inch growth spurt later, he found himself with the 1986 Detroit Piston “Bad Boys,'' where his signature flare began to light. Though he had experienced success with the Pistons and was no longer that doomed kid from the Dallas projects, Rodman still felt something vital was missing, as if something were out of place. On a particularly tumultuous night, he considered suicide. He made a deal with himself: go on living but abandon the manicured facade. Don’t end Dennis Rodman but only the “imposter” masquerading as him. This is the inciting incident in the story of his life; it’s how he begins his autobiography “Bad As I Wanna Be.” He lays out his inner monologue that night, asking:

“Did I want to be like almost everyone else in the NBA and be used and treated as a product for other people’s profit and enjoyment? Or did I want to be my own person, be true to myself and let the person inside me be free to do what he wanted to do, no matter what anybody else said or thought?”

That night, unlike many of his straight-laced PR devotee peers, Rodman chose to deny becoming a product—a monetized entity rather than a fully-fleshed human being. From this decision came the boisterous, bejeweled Dennis Rodman who has since etched his place in fashion history.

Rodman corrupting late night host David Letterman with a can of green hair spray. Image courtesy of Getty Images, Alan Singer/CBS.

Throughout the ‘90s, Rodman’s stardom grew right alongside his athleticism. For the uninitiated, Rodman was consistently one of the most dangerous and formidable players on the court. He was hailed a defensive savant and arguably the best rebounder in NBA history while on the dominant Chicago Bulls team. Rodman’s celebrity status was also rising. Boundary-pushing pop star Madonna, who was also Rodman’s two-month tryst, was reportedly willing to pay $20 million to have his baby. His flamboyant style persevered despite seas of speculation about his sexuality (and sanity). Criticism laced with misogynoir that labeled him as the industry “f*ck up” fell short with one glance at his integral part in three consecutive Bulls championships. You can’t argue with results, and the results confirmed that Dennis Rodman, the shimmering boa-ed basketball freak, was here to stay.

Rodman refused to compromise any one aspect of his personhood for appearance or digestability’s sake, creating a marbled joke out of tidily segmented “work-life balances.” His enigmatic multiplicity skillfully deflected any attempt at boxing in, electing, instead, to carve out its own vision.

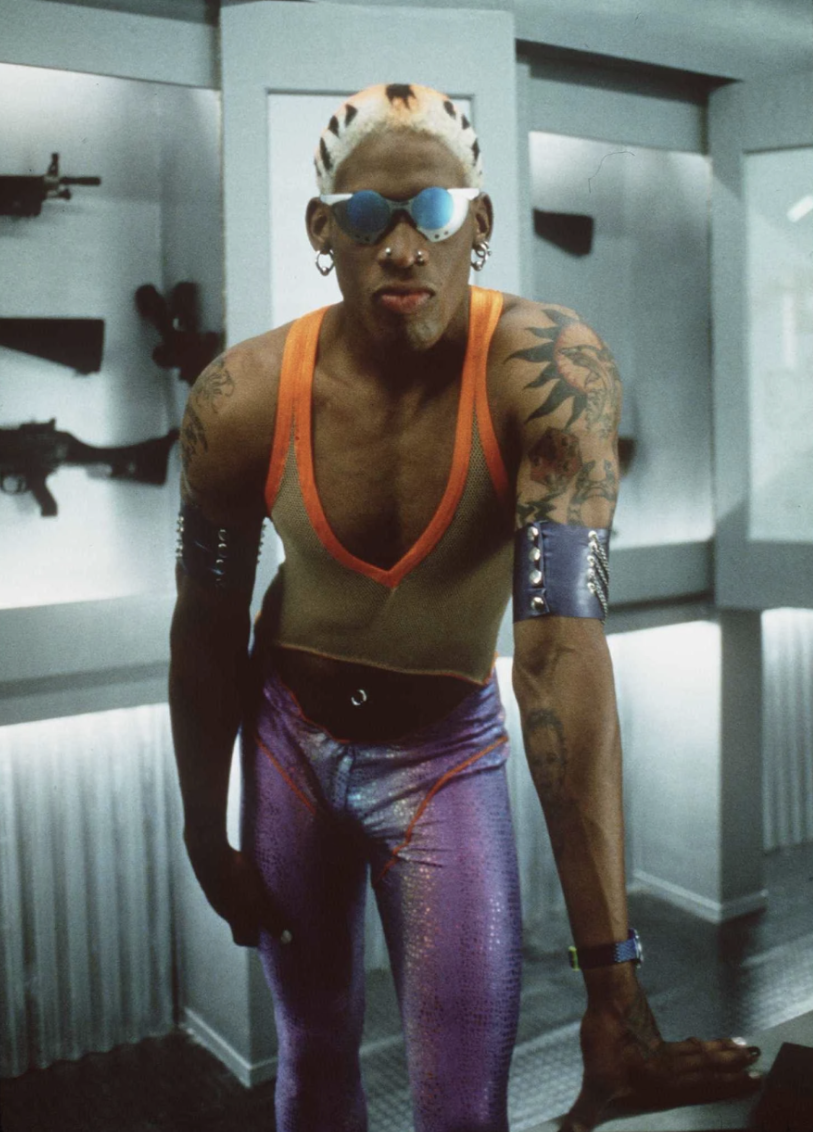

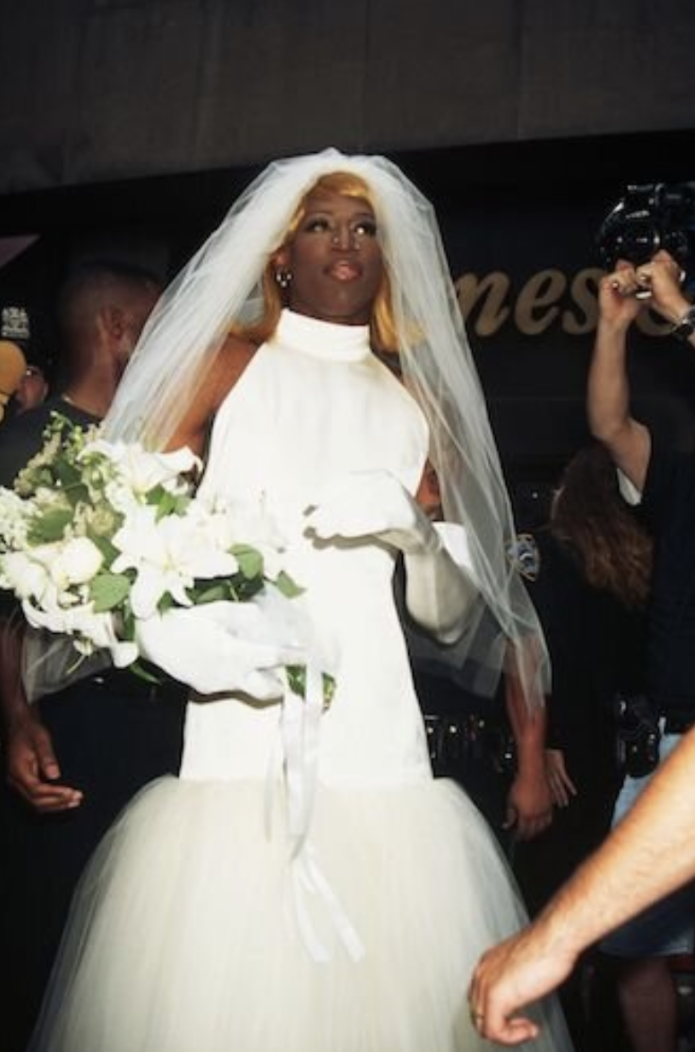

However, it’s hard to blame skeptics who questioned his motives because of just how unprecedented a character like Rodman was. Although subcultures like grunge, goth and hip hop were on the rise, to see a black athlete with such widespread publicity so shamelessly participate was entirely unique. He represented an almost pervasive diversion from the cookie-cutter pop culture icon mold by indulging in nonconformity. But Rodman’s adoption and circulation of counter-cultural trends, like drag-inspired looks, daytime negligees and having enough conspicuous body modifications to be seen from the International Space Station, was not ulterior in the slightest. Moreover, Rodman actually invested in and supported the countercultural groups he mirrored. He was frequently spotted partying in gay nightclubs and was an advocate for AIDs Awareness when comprehensive HIV education was more lacking than it is today. He embraced the mutuality between him and all the other outcasts of the ‘90s.

This sincerity of self was alluring to the public nearly three decades ago, and it’s why we’re still so retrospectively enamored with him now. In a culture where authenticity seems to be waning, Rodman’s pension for nihilistic self-confidence looks increasingly desirable. His obliteration of gender and racial boundaries blazed a trail for all oddities. Or, if anything, he’s at least prepared us for “Soundcloud Rapper Chic” and resident “Scumbro” Pete Davidson doing this.

Of course, the story of “America’s most provocative athlete” is much more substantial than what’s told here, and it includes unsavory anecdotes, namely his more than bizarre best friendship with fascist dictator Kim Jong Un. (I know, I know. Non-sequitur doesn’t even begin to cover it.) Even so, Rodman still occupies an incomparable space in the annals of fashion history; he materialized his outcast status and individuality into his physical perception and made tangible his abstractness. He was unflinchingly singular in his multiplicity and used personal style to find comfort in the outrageous.

Image courtesy of Getty Images, Mitchell Singer.

Rodman at the 1995 VMAs red carpet wearing an HIV/AIDs Awareness Ribbon. Image courtesy of Getty Images. Photo by Ron Galella, Ltd./Ron Galella Collection.