A Stitch in Time: When Outrageous Hats Were all the Rage

Graphic by Ruth Ellen Berry.

Most of the hats I see paraded around nowadays on passerbys' sun-protected heads are baseball caps, beanies or sun hats. And, while these hats have their merits, I can’t help but wonder what it would be like to exist in the days where hats were more than just a quotidian, handy accessory — the days in which hats stood ostentatiously high and elaborate on the head, boasting plumes and all sorts of fabrics and lined with meticulously sewn decorations. Could you image the kind of attention someone would attract nowadays if you saw them crossing the street with hats like these:

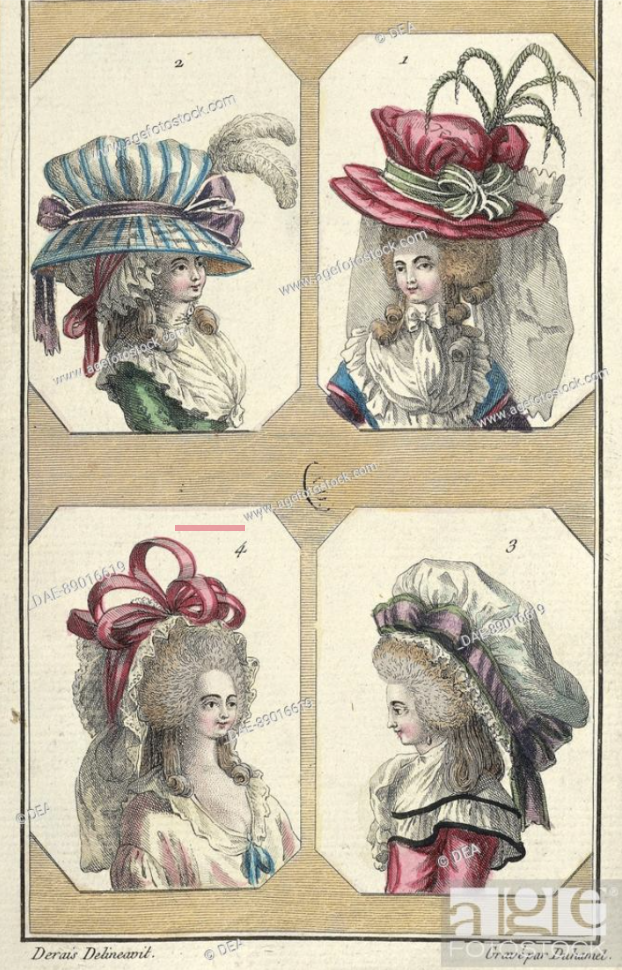

Images courtesy of Amesbury Carriage Museum (first), Click Americana (second) and Age Foto Stock (third).

Hats like these haven’t entirely been swept off the face of the earth (visit the Kentucky Derby and you might become acquainted with some of these showstoppers). Still, they aren’t nearly as prevalent as they once were.

During the Renaissance, with the arrival of humanism, trade and wealth and the prevalence and advancement of visual art, extravagant fashion bloomed. Materialism and a focus on the appearance of the self grew more prevalent. In late-medieval and Renaissance Europe, women began to wear hats more conspicuous than ever before. For instance, hennins, a type of tall, conical hat attached to a veil, were worn by some women during this time.

Image courtesy of Smithsonian Magazine.

Other women’s styles, decorated with silk, gold and pearls and shaped into large, imposing structures, also reigned the hat world in Europe during this time. In fact, laws were put into place to restrict the materials, sizes and number of women’s hats in order to put a check on the extravagance of such hats. Catholic churchmen even prompted their followers to hurl insults at women wearing such ostentatious hats. This was only part of a larger trend of women being barraged with criticism for elaborate choices regarding fashion not only in general, but particularly in the case of hats.

Marie Antoinette, whose appetite for luxury and fashion earned her disapproval from her contemporaries and insults in the press (who described her as made for the role of mistress rather than wife), was the client of famous milliner Rose Bertin. Bertin was an internationally famous milliner who designed different styles of elaborate hats adorned with feathers, ribbons and laces.

While white lace-wired, feathered and beaver hats were prevalent in the 17th century, hat styles in the 18th century continued to grow and change. Hats grew in importance and popularity in the fashion world during the second half of the 18th century. The Rococo period emphasizing the lighthearted and elaborate lives of aristocracy influenced the fashion world, increasing embellishments. Throughout the 18th century, the extravagance of women’s hats was written about and satirized by critics.

In the 19th century, a growing middle class and an increase in physical leisure activities led to some women’s hats styles adopting the design of menswear. More simple, athletic designs rose in popularity, but nevertheless, fancy hats adorned with plumes persisted. And they continued to persist into the early 20th century, which became quite a problem for moviegoers. You see, these outrageous women’s hats took up quite a bit of space and had a habit of obstructing movie screens. And women’s 20th-century hats were growing more extravagant still, decorated with more plumes, fruit baskets even, and miniature barnyard animals.

In a 1909 article recounting the obstacles women’s hats posed to 1900s movie theaters, a film journalist wrote, “The eternal feminine hat is always a source of much irritation to mere man…In this regard the average woman is quite a savage person. It is a matter of pure indifference to her as to how much inconvenience the person sitting behind her may be put by the wearing of her hat.” I certainly laughed while reading this quote the first time around, but women weren’t only met with ridicule for their hat choices during the early 20th century, they were also made to be the symbols of capitalism’s extreme wealth. Perhaps rightly so because women’s hats could rack up quite a price, and they were extravagant, and they were outrageous, at times.

However, fashion for women has not always been such a frivolous, extravagant thing nor the product of too much money and no place to put it. In times when upper-class women did not have access to adequate education, or jobs in the traditional sense, or even pastimes that weren’t tedious, there was fashion. And, there was some power and autonomy to be given to women through fashion. For instance, when Nazis occupied Paris in the second world war, French women lifted their spirit and confidence and showed defiance by wearing scraps in wild configurations on their heads as the fashion industry suffered from rationing.

I watched a video once of a fish collecting shells and placing them in a pile on the sand — its very own collection. I was in awe that it found pleasure or meaning or something of the sort in the act of placing shells together. When I look at such extravagant hats, I can’t help but think of how people have created their own collections of pretty objects and placed them together in piles on top of heads, finding purpose, pleasure or fascination in that.

Image courtesy of Insider.

Whether history’s outrageous hats are providing means of personal expression or protest, starting trends or sparking up controversy, they’ve drawn attention and left impressions as big as their forms.