Another Incredibly Styled Movie by Gregg Araki: The Typical and the Surreal

Graphic by guest designer Tori Wilkins (http://toriwilkins.com).

Our generation is gonna witness the end of everything. You can see it in our eyes. It’s in mine. Look, I’m doomed.

Dark, “Nowhere” (1997, Gregg Araki)

The ‘Whatever Girls’ from “Nowhere” (1997, Gregg Araki). Image courtesy of Fine Line Pictures.

Any outfit is an extension of one’s persona. This concept rings truest in the world of cinema, where every minute detail is curated to support a creative vision. The cinematography of independent filmmaker Gregg Araki certainly falls in this category. His cult-classic star-studded hit from 1997, “Nowhere,” which he has described as “‘Beverly Hills, 90210’ on acid,” along with other standouts in his filmography, mix the supernatural with the mundane –the real with the surreal. His creative playground revolves around the concepts of doom, hopelessness, apocalypse and adolescence, and his film styling is an extension of these themes. Let’s look into Gregg Araki, adolescent doom and how styling connects a movie to its message.

“Nowhere” (Gregg Araki, 1997). Images courtesy of Fine Line Pictures.

Araki’s 82-minute trip sequence “Nowhere” was the last installment of his so-called “Teenage Apocalypse Trilogy,” grouped alongside the titles “Totally F***ed Up” and “The Doom Generation.” One of his most infamous films to date, “Nowhere” features a hyper-saturated grab-bag of stylistic choices. On paper, the film’s plot is just a gaggle of polyamorous sex-crazed and substance-abusive LA teens on a quest to the party of the century, but woven into that “Dazed and Confused”-esque anti-plot is an apocalyptic, existentially dreadful subplot. Araki, a prominent figure in the New Queer Cinema wave, often centers his films around the triumphs and plight of disillusioned queer youths during the fall-out of the AIDS epidemic of the 90s. The very real pressures and nonsensical brutality of that era manifest in his films as alien abductions and bloody cockroach metamorphoses, to name a few. His settings become purgatorial wastelands filled with a general unease and a “lost” feeling that crescendos to a breaking point at the climax of each movie. In this way, any Araki film is at once surreal in its presentation and startlingly hyperreal in its subject matter– a simultaneous scathing critique set in a dreamscape (or hell-scape, as it were). Araki is a master of mending these two categories to settle on his message, and his film costuming contributes to this skill.

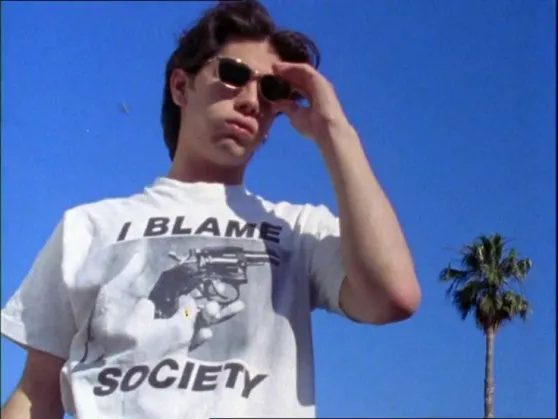

The wardrobe (SaraJane Slotnick) and hair/makeup (Jason Rail) of “Nowhere” include the prototypical sun-soaked 90s teen line-up of graphic tees, baggy cargo capris, miniskirts and matching sunnies. However, Slotnick and Rail, executing Araki’s vision, elevated these tropes to surreal heights. Typical outfits and stereotypes of superficial LA residents are saturated to a cartoonish degree, hence the hallucinogenic “90210” comparison.

Still of ‘Val-Chicks 1-3’ from “Nowhere” (1997, Gregg Araki). Image courtesy of Fine Line Pictures.

“Nowhere” (1997, Gregg Araki). Image courtesy of Fine Line Pictures.

In the same way Araki’s films do not explain or reconcile the weaving of the natural and supernatural in the plot, they also do not explain the uncanny, fever dream-ish appearance of the characters and sets. Heavily teased and dyed wigs, queer-coded garb, clashing fabrics/patterns/hues and a general “dressing-for-the-back-of-the-room” vibe all litter Araki’s movie styling techniques. Amy, one of the main characters in “The Doom Generation” (1995), is pointedly rebellious through her wardrobe choices, which include chunky silver jewelry, big black combat boots, oversized shades and the letters “K-I-L-L” inscribed on her knuckles. Araki’s characters embrace their singularity and necessary apathy against their encroaching oblivion through their appearance. What’s the harm in looking like you stumbled into some retro-futurist's closet and put on the first thing you saw if your reality is crumbling and you could get vaporized by a reptile alien at any moment?

“The Doom Generation” (1995, Gregg Araki). Image courtesy of Trimark.

“Mysterious Skin” (2004, Gregg Araki). Image courtesy of Tartan Films & TLA Releasing.

“Totally F***ed Up” (1993, Gregg Araki). Image courtesy of Strand Releasing.

Beyond making many of his characters look like they watch “The Fifth Element” for outfit inspo, Araki’s stylistic choices in his films serve both as indicators of non-conformity and over-saturated interpretations of real teen nihilism and existential dismay. The characters’ personas become, just like the plots, typical and surreal at the same time. The director uses this heightened version of our world and translates its nonsensical absurdity into these visuals to capture the psychic pressures we all face. We, in the real world, may not be at the wrong end of some alien race’s vaporizer gun (heavy on the may), but we might as well be. In Araki’s view, we are logical beings living in a world to which no logic can be applied. Teens and young adults, being newly thrust into that world and unable to remedy it, are often left feeling alienated, hopeless, doomed. Araki perfectly captures this feeling of imminent Armageddon through creating surrealities, little pockets of extravagance in his characters’ apocalypse.

“Nowhere” (1997, Gregg Araki). Image courtesy of Fine Line Pictures.

“Now Apocalypse” (2019, Gregg Araki). Image courtesy of Starz.

“Here Now” (2015, Gregg Araki). Image courtesy of Kenzo.

“Nowhere” (1997, Gregg Araki). Image courtesy of Fine Line Pictures.