Festival Fashion: An Analysis

Graphic by Isabelle Hauf-Pisoni.

“Music festival” feels like an inadequate term to describe the all-encompassing experience that is Coachella or Lollapalooza or Glastonbury. More than just music itself, music festivals are platforms for self-expression, fashion statements and status signaling. Outfits are painstakingly chosen, accessories prepared months ahead and paparazzi stationed at every corner to capture celebrity styles. Fashion has become inexplicably tied to music festivals, for better or worse.

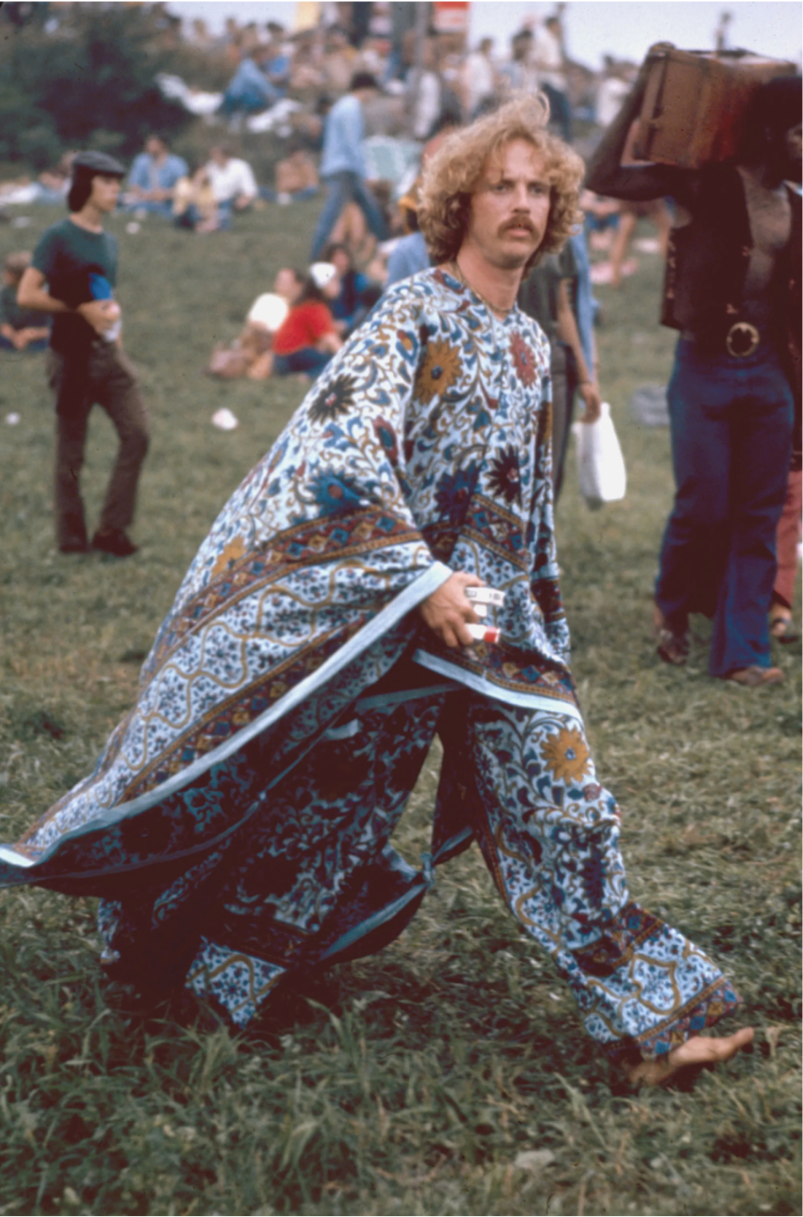

Festival fashion was born out of the countercultures of the festivals themselves. The crochet tops and denim bell bottoms of Woodstock signified its rebellion against the political climate and stifling uniformity of the 1960s; the oversized tees and battered Doc Martens of Lollapalooza paid homage to the punk rock legends that graced its stages; the glitzy co-ords and sleek streetwear of Electric Daisy Carnival perpetuated its energetic rave persona. Styles reflected the music itself, importing the personality of the festivals onto the clothes worn at these events.

But as music festivals have increased in prominence and in audience size, so have the expectations for the outfits that will fill their crowds. Anticipation for celebrity style choices have come to overshadow even the lineups themselves. A mere glimpse of Vanessa Hudgens’ Coachella manicure elicits thousands of Instagram comments and dozens of articles.

As festival outfits progressively populate social media feeds and commercial brands jump even more fervently at the chance to capitalize on their popularity, festival fashion has become its own style sector — its own tab on a brand’s website. This commercialization of festival fashion presents a peculiar paradox. After all, each festival has a unique dress code. An outfit that would fit perfectly at a country music festival like Stagecoach would feel uncomfortably out of place at hip-hop festival Rolling Loud.

Modern festival fashion choices are seemingly less about expressing the subculture and individuality that prompted the creation of festivals and more about enforcing its perceived aesthetic. But where do these aesthetics come from? And what do they indicate about the evolution and future of festival fashion?

The roots of festival fashion can be traced back to Woodstock: a three-day frenzy of defiance against gender stereotypes and celebration of self-expression, a sea of patchwork denim and tie-dyed bra tops and performances from music icons such as Jimi Hendricks and Santana, all on a small dairy farm in upstate New York.

Image courtesy of Vogue.

Woodstock’s influence on festival fashion is still prevalent. Its free-flowing, flowerchild, hippie mentality characterizes the fashion of festivals like Coachella and Austin City Limits. Yet, this romanticized reinterpretation of Woodstock fashion has manifested into something much more social media curatable and frequently problematic.

Take Coachella. Coachella was founded with the intention of becoming a more affordable music festival option, geared at uniting audiences of niche genres. Its Woodstock-esque inspiration seems fitting for its non-conformist origins.

Now dubbed the “Superbowl of fashion,” Coachella’s desert landscape has become a diamond mine for commercial brands, a battleground for influencers vying to have their outfits rack up the most exposure and a hotbed for cultural appropriation, especially of indigenous and Black communities. Adhering to and profiting off of Coachella’s overarching fashion expectations is often prioritized over individual expression, genuine connections to the music and even basic cultural sensitivity.

Image courtesy of The Mom Edit.

This isn’t limited to Coachella. Lollapalooza, arguably Coachella’s cooler, angstier older sister, began as a gathering place for rebellious, punk-obsessed teenagers. The festival’s more laid-back, grunge, skater style comes from its initial emergence as an alternative, punk-rock festival, hosting the likes of Kurt Cobain and Pearl Jam. This aesthetic, however, has become increasingly intentional. Many attendees put great effort into creating an “effortlessly” disheveled look. The often overwhelming expectation to dress a certain way, whether it be glittery rave gear at an EDM festival or boots and a ten-gallon hat at a country music festival, is a powerful guiding force for many attendees when choosing their outfits.

A large perpetrator of the uniformity of festival fashion has been its commercialization, a phenomenon that emerged in tandem with increased societal infatuation with celebrity. In 2005, Kate Moss strutted down the muddy campsite of the Glastonbury music festival in a sheer, metallic knit minidress and knee-high Hunter rain boots.

Image courtesy of Harper’s Bazaar.

The next year, Hunter opened up a (very successful) store in New York, and Kate Moss’s strategic footwear became a lasting Glastonbury staple. With hundreds of thousands of patrons at festivals and even more people at home repeatedly refreshing their feeds to see what festival-goers are wearing, music festivals present incredibly marketable opportunities for commercial brands. Labels have readily seized this celebrity-driven attention to exacerbate festival fashion’s increasing uniformity.

This isn’t to say that music festivals are hopeless pits of fast fashion, celebrity obsession and commercial exploitation. Music festivals offer a stage for authenticity and experimentation with fashion, and sometimes this overlaps with the general aesthetic of the festival. It's about the intentions behind the clothes and whether they are based on individuality and genuine style choices rather than a looming pressure to live up to preconceived festival expectations or blend into an increasingly uniform Instagram feed.

The influencer-era is not the end-all-be-all for festival fashion—musical festivals don’t have to be trapped within their own aesthetic. Innovative and thoughtfully designed music festivals, such as Afropunk—a festival celebrating Black punk culture—mark a step in the right direction, signaling a much-needed divergence from the cultural appropriation and oversaturated commercialization that often plagues festivals and their fashion. Self-expression and festival fashion are not mutually exclusive entities. In fact,when looking at the origins of music festivals, they actually go hand-in-hand.