Finding our Place Among the Stars: Modern Sci-Fi and the Fantasy of Afrofuturism

It’s 2013. I’m 9 years old, and the young adult dystopian novel craze is taking over my midwestern town. “The Hunger Games” quickly becomes my favorite series, and I’m anticipating the “Catching Fire” adaptation more than summer camp or even soccer season. The budding teen sci-fi, dystopia genre fascinates me because the imagined worlds seem so fantastical. ”The Hunger Games” follows a teenage archer and a mousy baker who team up to overthrow a syndicate of campy fascists. What morbidly bored fly-over-state preteen wouldn’t count down to its release date?

But by ninth grade, those stories started to lose their luster. I realized that the culprit of my disinterest was deeper than my usual tendency to quickly tire of hyperfixations or my growing reliance on technology. Young adult dystopian novels are often about a marginalized person or group’s fight for liberation. When I was in third grade, Katniss Everdeen and her carefully copied –– or more generously, inspired–– counterparts (“Divergent,” I’m looking directly at you) were my most salient representations of rebellion. I soon realized that the stories white consumers often consider to be dystopian are not actually fictional; they are structured around the struggles that Black people and other oppressed groups have had to endure for centuries.

These authors echo Civil Rights-era rhetoric slamming classism and injustice while completely whitewashing its clientele, rendering Black people hypothetically extinct. The essence of Black struggle –– neatly translated onto futuristic fair-skinned, heterosexual and abled bodies –– is titillating enough to hold the attention of an entire nation, yet our ongoing, real-life fights are not. On a quest for answers after the decline of the teen dystopia era and following my own personal pivot towards racial empowerment, I stumbled upon Afrofuturism.

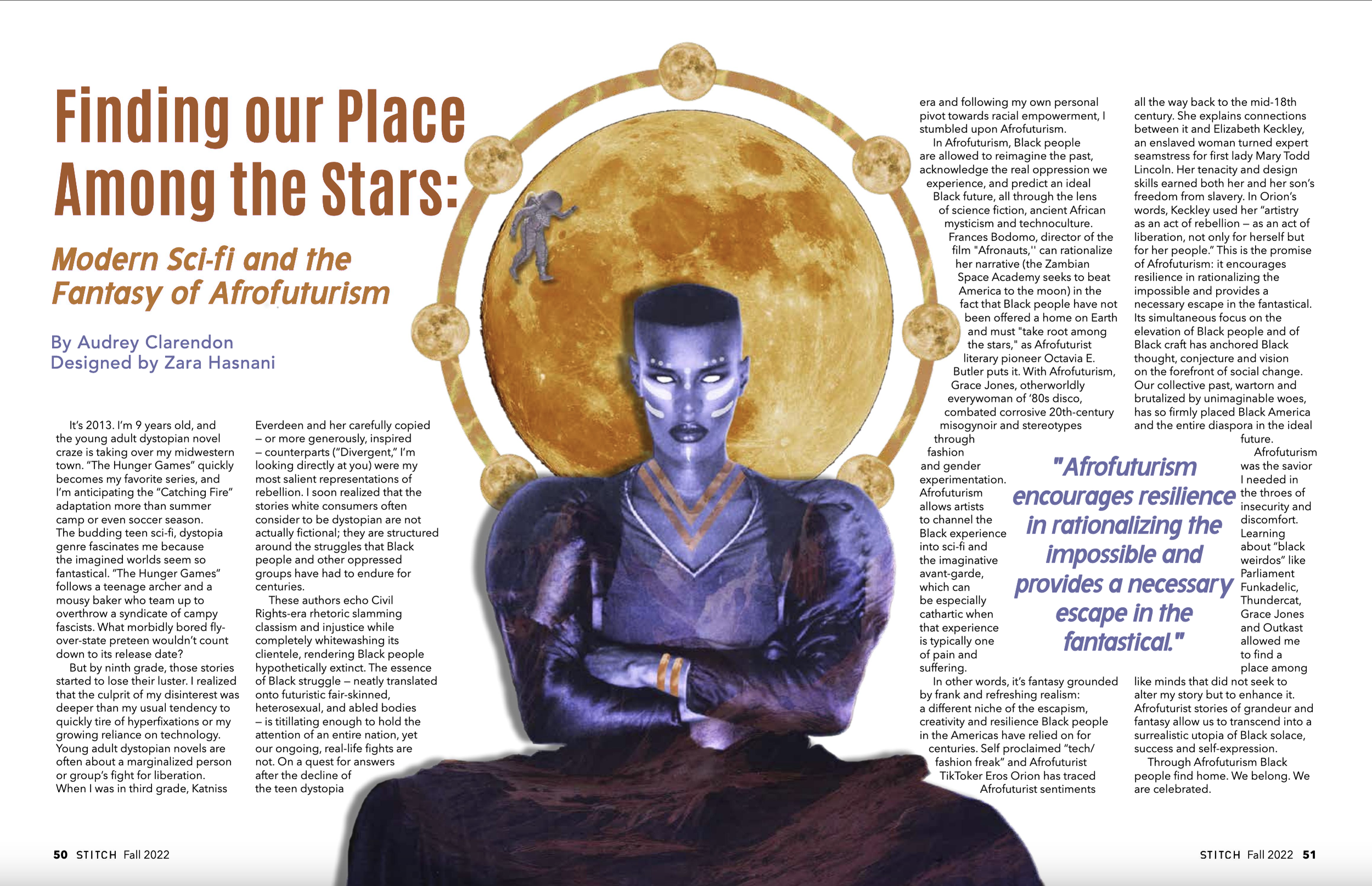

In Afrofuturism, Black people are allowed to reimagine the past, acknowledge the real oppression we experience, and predict an ideal Black future, all through the lens of science fiction, ancient African mysticism and technoculture. Frances Bodomo, director of the film "Afronauts,'' can rationalize her narrative (the Zambian Space Academy seeks to beat America to the moon) in the fact that Black people have not been offered a home on Earth and must "take root among the stars," as Afrofuturist literary pioneer Octavia E. Butler puts it. With Afrofuturism, Grace Jones, otherworldly everywoman of ‘80s disco, combated corrosive 20th-century misogynoir and stereotypes through fashion and gender experimentation. Afrofuturism allows artists to channel the Black experience into sci-fi and the imaginative avant-garde, which can be especially cathartic when that experience is typically one of pain and suffering.

In other words, it’s fantasy grounded by frank and refreshing realism: a different niche of the escapism, creativity and resilience Black people in the Americas have relied on for centuries. Self proclaimed “tech/fashion freak” and Afrofuturist TikToker Eros Orion has traced Afrofuturist sentiments all the way back to the mid-18th century. She explains connections between it and Elizabeth Keckley, an enslaved woman turned expert seamstress for first lady Mary Todd Lincoln. Her tenacity and design skills earned both her and her son’s freedom from slavery. In Orion’s words, Keckley used her “artistry as an act of rebellion –– as an act of liberation, not only for herself but for her people.” This is the promise of Afrofuturism: it encourages resilience in rationalizing the impossible and provides a necessary escape in the fantastical. Its simultaneous focus on the elevation of Black people and Black craft has anchored Black thought, conjecture and vision on the forefront of social change. Our collective past, wartorn and brutalized by unimaginable woes, has so firmly placed Black America and the entire diaspora in the ideal future.

Afrofuturism was the savior I needed when I was in the throes of racial alienation and insecurity. Learning about “black weirdos” like Parliament Funkadelic, Thundercat, Grace Jones and Outkast allowed me to find a place among like minds that did not seek to alter my story but to enhance it, unlike misrepresentative white dystopian narratives. Afrofuturist stories of grandeur and fantasy allow us to transcend into a surrealistic utopia of Black solace, success and self-expression.

Through Afrofuturism Black people find home. We belong. We are celebrated.