The Body as an Accessory: Where to Turn When Your Clothes Begin to Wear You

A look at how body types have come in and out of style.

I’ve been in love with F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel The Great Gatsby since high school. Everything about it, from the inflated egos to the bloody demise of Gatsby, is just so outrageously fantastical, so utterly unbelievable, that Fitzgerald’s world becomes something of a pipedream. But when I first watched Baz Luhrmann’s 2013 film adaptation, I was saddened, though not surprised, by the lack of body diversity.

Jordan Baker, played by the tall, slender Elizabeth Debicki, is presented as the ultimate flapper. We first see her in a silk, champagne-colored tank, baggy slacks and layered pearls blending perfectly with the fluttering curtains. Later, she reappears at Gatsby’s party in a navy, open back evening gown.

Debicki’s figure seems to perfectly suit the flapper style. Although this observation may seem rather trivial — almost obvious — its perceived “obviousness” got me thinking. Why do certain female bodies seem to just fit different styles? Why do we associate flapper dresses with lanky limbs, poodle skirts with defined curves, and low-rise jeans with a thin frame?

To put it quite simply, it’s because the female body has historically functioned as an accessory. Beauty standards shift with fashion trends, and the reality of bodily commoditization takes hold.

Androgynous Allure with a Touch of Chanel N°5

Given that silhouette and style are intrinsically connected, it is no surprise that Debicki was chosen to play the rebellious Baker. In the ‘20s, clothing with simple lines and androgynous shapes was favored. It was fashionable for not only women’s clothing, but also their bodies, to appear straight and lanky. Through exercise, diets and undergarments, many women were able to achieve this shape.

La garçonne style, translated literally as “the man style,” encapsulates the way women aspired to dress and act in the ‘20s. Abolitionists and suffragettes paved the way for first-wave feminism. Women were taking on new roles in society, including voting, working, driving and even smoking in public. Consequently, they wanted a less physically restricting wardrobe to enjoy these freedoms.

Androgynous styles were the perfect option. Flappers embraced la garçonne by wearing high waisted dress pants, cloche hats, scarves and dresses that resembled loose fitting suits. Coco Chanel led the way with her tweed suits, little black dresses and iconic fragrances for a dash of femininity.

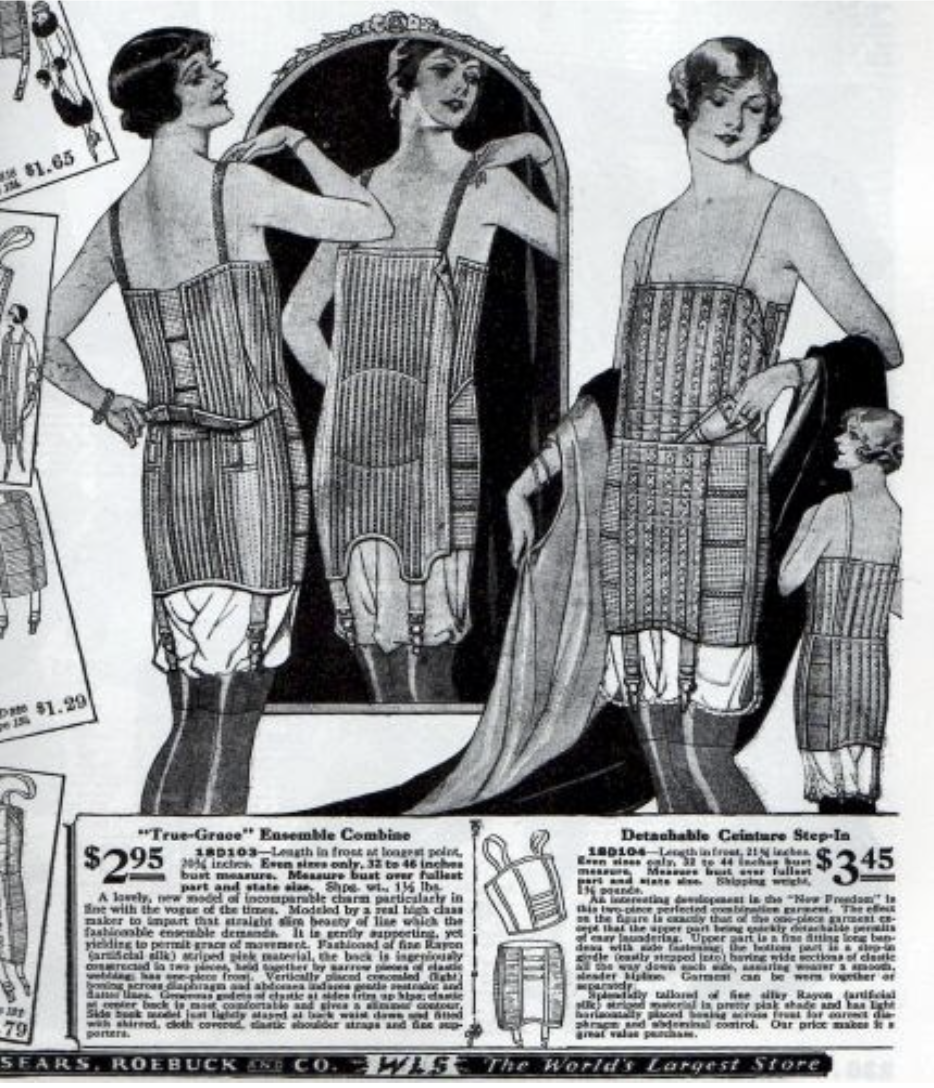

Boxy, formless shapes rose in popularity alongside a very thin, athletic, almost boyish build, like that of Debicki. Curves were very much “out.” Rather than modern-day Spanx and Skims, which guarantee a cinched waist and smooth curves, aspiring flappers forced themselves into front lacing corsets and bust confiners. The former was meant to achieve a completely straight waist, and the latter, a flat chest.

Dior to Dyson

The clock is always ticking, especially in the fashion world. The flapper-era was fleeting, and by the late ‘40s, curves were back in style. Christian Dior’s New Look collection was instrumental in reviving a more classic, Victorian-era style that dominated the post-World War II eurocentric world. His titular “New Look” included billowing A-line dresses, cinched waistlines and padded hips along with plenty of frills and pleats.

After a decade of practical dressing due to wartime restrictions on fine fabrics, this collection celebrates a fresh start, ultra-femininity and opulence. Although Dior’s “new outlook” may not have resonated with everyone, namely feminists who found a return to old ways oppressive, it caught on quickly with the general public. By the mid-’50s, women everywhere — from homemakers to Parisian socialites — sported these Cinderella dresses and wanted to create the illusion of a tiny waist too.

The ‘50s were a time of social and political conservatism, especially in the U.S. White picket fences, suburbia, strictly imposed gender roles and a romanticization of motherhood supported Dior’s vision of a blissful yesteryear. Without the flapper dress, there was no longer a desire for a boyish figure, at least within the fashion sphere. A defined waist and fuller bust could more effectively convey the Victorian gentility that was mid-century fashion.

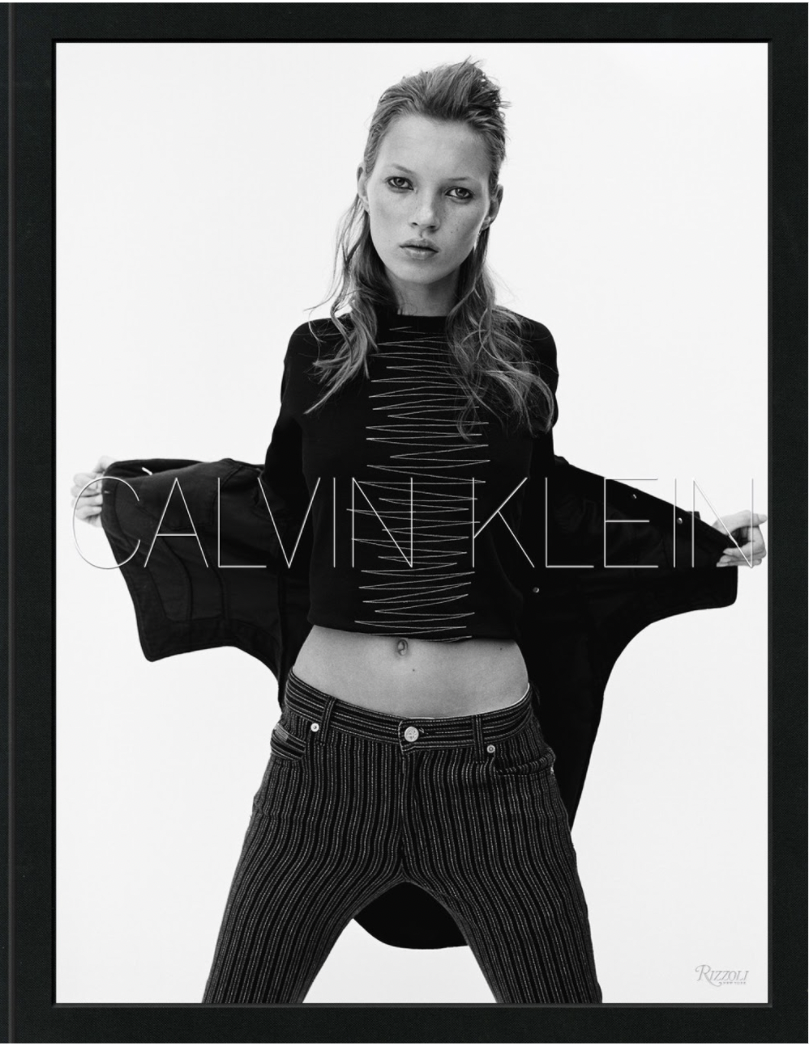

Moss and Minimalism

Fast forward to the mid-’90s. The Big Five supermodels — Cindy Crawford, Naomi Campbell, Christy Turlington, Linda Evangelista and Claudia Schiffer — began to take a backseat to a British model, Kate Moss. Her pale complexion and waif-like frame ushered in “heroin chic” — an unfortunate name for an era that glamorized looking malnourished. Fashion houses took the heroin chic trend to extremes by hiring models with visible rib cages, bags under their eyes and bruises covering their bodies. Consequently, a connection between unhealthy thinness and high fashion quickly emerged.

Moss’ work with Calvin Klein glorified minimalism, which was a core tenet of this time. Neutral tones and grungy plaids were sexy and chic. The ever-polarizing low-rise jeans made their first appearance in the ‘90s but didn’t reach extreme levels of popularity until the latter half of Y2K. Scarf wrap tops, spaghetti straps and slip dresses were omnipresent, much like they are today. These styles provided minimal coverage and tended to be modeled by women who were small all around. Fashion’s infatuation with litheness and bareness propelled trends like the slip dress and muted color schemes. In many ways, the late ‘90s epitomized what it means for the body to be an accessory. A woman’s physical shape was forced to become part of the garment’s story because the actual designs were so ... lacking.

Wear The Clothes, Don’t Let Them Wear You

Conforming to “body trends” is an impossible endeavor, and one that is both physically harmful and detrimental to maintaining a positive body image. It’s important to separate fashion trends from the body because your body is not an accessory. It can never go out of style. Fashions are meant to be enjoyed, embraced and worn by everybody.