The Curated World of Wes Anderson

Graphic by Agnes Lee.

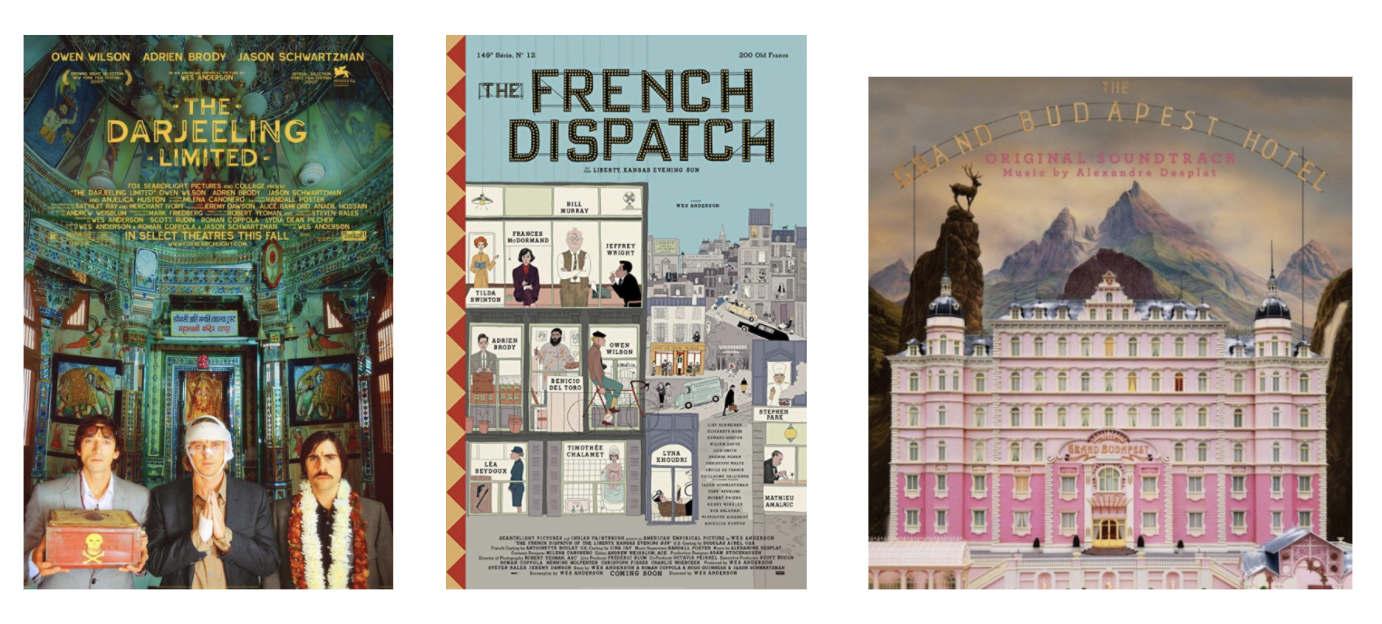

When you walk down the multicolored carpet hallways of a movie theatre, the large posters lining the walls include the usual suspects: superheroes staring intensely against a backdrop of red and blue, a Hollywood star who closely resembles the historical figure whose life story they will enact, and the stars of the latest rom-com standing back to back. But once every few years something different catches your eye. Something like an ornate building resembling a dollhouse with intriguing characters in the windows. You’re compelled to take a second look, for you’ve caught a snapshot of Wes Anderson’s perfectly curated world –– one he designed just for you.

Watching one Wes Anderson movie is enough to pick up on his distinct aesthetic. The sets are colorful, playful and filled with eye-catching details. The star-studded casts include repeat players, such as Frances McDormand, Owen Wilson, Tilda Swinton and Bill Murray. Camera angles capture the actors from their side profile or head on. Symmetry and asymmetry play a big role in set design. Characters often wear one costume throughout the movie, as if in uniform.

Combined with the quirk, humor and heart that fills the storylines of Anderson’s movies, his ability to please the eye has given his films a cult following. The way that he creates a memorable and unique viewing experience for the audience is through intention. We see what Anderson wants us to see.

How do these films captivate audiences so effectively? I decided to find out by watching his newest release, The French Dispatch, with a fresh pair of eyes. Set in the small French town of Ennui-sur-Blasé, the plot includes three stories covered by an outpost of a Kansas newspaper called “The French Dispatch.”

Every detail in Anderson’s world is a creation. Ennui-sur-Blasé is a fictitious town, but the events that transpire there hardly evoke the boredom the town’s name might suggest. The plot details three journalists’ accounts of events taking place in the town: a prisoner’s ascent to fame after creating abstract paintings of the female figure, a student protest over whether boys should have access to the girls’ dormitories and a private dinner with the Commissaire of the Ennui Police, which is disrupted by the kidnapping of the Commisaire’s son.

Anderson wrote the screenplay for The French Dispatch, but his flair for the extraordinary extends beyond his plotlines and into aesthetics.

Like the films that preceded it, the world of The French Dispatch is distinctly its own. Each element of the set design can be recognized for what it is meant to be — an old apartment building, a prison cell and a local cafe — but is unmistakably a construction built by Anderson and his team. Buildings have a fakeness akin to a dollhouse; interiors are decorated with objects and symbols that are significant to the characters and the story; and symmetry and asymmetry guide the viewer’s eye to specific details. There is no doubt that what you notice is meant to be noticed.

Photos courtesy of Architectural Digest

Photo courtesy of Little White Lies

This trend continues with the costume designs. The office employees at “The French Dispatch” wear pastels and muted tones, which complement the lemon yellow walls, wooden furniture and burnt orange accents in the cabinetry, picture frames and books. The journalists’ outfits also juxtapose the office space’s busyness: the simple collared shirts, sweater vests and pleated skirts need no additional frills when placed alongside the maximalist office space.

One of the most visually striking costumes belonged to Tilda Swinton’s character, J.K.L. Berensen, who gives a lecture about the Ennui prison artist. She draws attention in her flaming orange, feather-print gown that complements both her red hair, the rust colored background and the character’s flair for drama.

Another memorable costume was that of Juliette, played by Lyna Khoudri. The most vocal opponent to the schoolboys’ protest, she was never seen without her motorcycle helmet on. Juliette never had her guard down and frequently butted heads with Zeffirelli, the leader of the boys’ “Chessboard Revolution.” With her helmet, Juliette was always ready to go on the offense. As is typical with many Anderson films, characters often wear one costume throughout the film. This consistency offers a level of iconography to the characters and for the audience, and it continuously reinforces their identities.

Tilda Swinton as Berenson; Photo courtesy of Monopol Magazin

Lyna Khoudri’s Juliette; Photo courtesy of Coup de Main

Anderson also made the choice of flipping back and forth between shooting in black and white and color. These scenes present a unique opportunity with respect to costume design. Anderson’s signature color coordination can no longer be used, adding to the importance of texture.

Photos courtesy of GQ

Saoirse Ronan, who plays a showgirl, wears a long, sheer dress as she talks to the kidnapped Commisaire’s son. An unnamed character, we know little of the showgirl aside from her profession. The dress communicates this, the black and white filter revealing nothing more to us than the dress’s sheerness, it’s intent to show the silhouette of her body.

The audience can see another strong contrast of texture and color when the prisoner stands beside the guards. The prisoner’s white sweater and pants appear to be made of simple fabric. The clothing is plain and little texture is visible to the audience, symbolic of how little he has in prison. Nothing distinguishes him from the others, contributing to their atomization. In contrast, the guards on either side of him wear black uniforms, tailored and structured. They have collars, shiny buttons down the middle and their names stitched to the breast pocket. Similarly, the two guards’ uniforms are almost identical, though not exactly. Unlike their prisoners, they are allowed small amounts of personalization.

Knowing that we are being led by the film’s creators to pay attention to details both big and small, whimsical and deeply symbolic, is what makes a Wes Anderson film uniquely enjoyable to watch. Your task as an audience member is to sit back and enjoy a guided tour through a special world — one that you can return to upon rewatch and continue uncovering. If you haven’t had the chance to explore Anderson’s films for yourself, The French Dispatch is your chance to start.