The Incredibly Gay History of Manly Clothes

Graphic by Isabelle Hauf-Pisoni.

Though it’s a chilly winter in Chicago, summer has been on my mind. During the summer of 2022, we witnessed the return of jorts, white tank tops and trucker hats. What was once a traditionally blue-collar uniform was now seen as fashion.

By the end of last year, these styles made it to the mainstream and were adopted by almost everyone. My Instagram feed was filled with gigantic denim shorts and similar throwback fashion choices.

This is the comeback of hyper-masculine clothes. At a time when gender-fluid dressing is normal, the old-fashioned American man is on the rise. Except this time, the traditional concept of masculinity is being championed by gay men.

Photos courtesy of @Drumaq (left) @RickeyThompson (right).

I’ve seen gay influencers, and their queer-baiting counterparts, donning this blue-collar chic for the past year, and it has become one of the most intriguing fashion trends. Athletic jerseys, camo patterns and workwear-oriented clothing have skyrocketed in popularity.

The style is practical and perfectly silly. People are taking otherwise unfashionable choices and turning them into fashion statements.

It’s empowering to see queer men own a traditional sense of masculinity. They are simultaneously asserting their own manhood while also redefining what a man really is.

Legacies of homophobia have stereotyped and emasculated queerness, but through an inconspicuous trend, queer people can announce their identity and challenge societal preconceptions.

A gay man dressed in jorts and a white tank is more provocative than it may appear. For starters, the style is ironic and campy. Queer men are riffing on masculinity and playing into the extremes. They’re using the clothing as a costume to subvert masculinity. Seeing queer people in varying degrees of masculinity creates beautiful diversity.

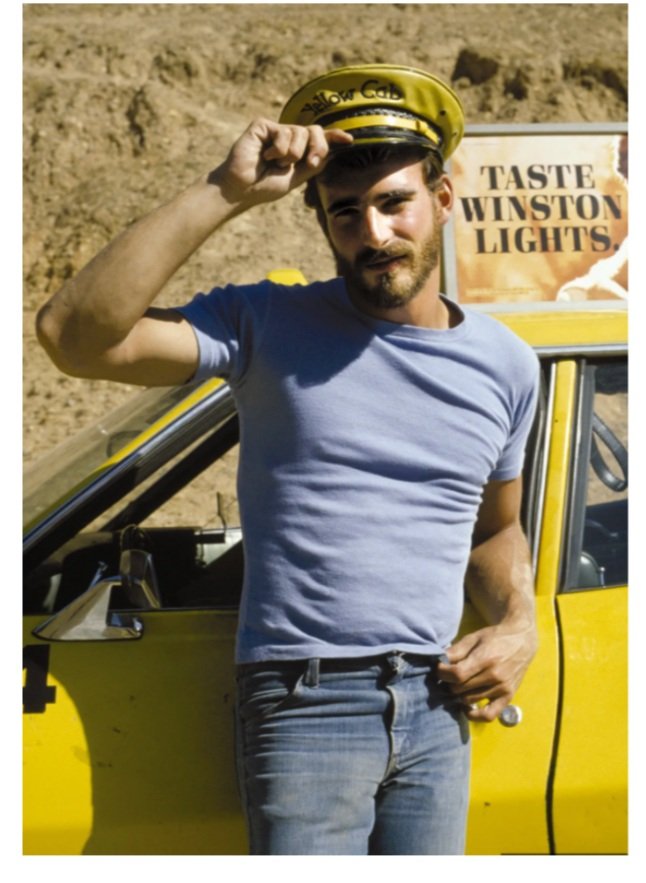

This is not the first time the gay community created a uniform to physicalize their identity. In the 1970s after the Stonewall riots, the Castro clones style was popularized. The clones donned tight Levi’s, flannels and body-hugging shirts. The trend was named after San Francisco’s Castro District — a predominately gay neighborhood where the style originated.

The imagery of gay pornography, the wild west and other Americana traditions influenced the clones' style, which lends to an erotic aesthetic. It emphasized masculine features, and played in the fantasy of rugged rural men, even though those who wore it were middle-class city dwellers. Castro clones were also masculine presenting enough to be passable in non-queer spaces. It was a uniform derived from code-switching in a heteronormative society.

Photo courtesy of GQ (Right).

After the Stonewall riots, the Castro clone was among the first dress codes that defined the gay community. It was a uniform that was instantly recognizable.

While gay men dressing in masculine ways can combat gay stereotypes, it also reveals internal homophobia within the queer community. Gay men idolize white, masculine-presenting men more than they do effeminate men. It’s a challenging dynamic that existed with the Castro clones, and it still persists today. The clone part of the name caught on because of how many gay men were copying the look nationwide. The clothes unified gay men but also exposed the assimilation, even among a community of outsiders.

I see the modern take on the Castro way of dress as much more about play than about conformity. Style has become increasingly expressive since the late 70s, and gay men don’t need to prescribe to a designated uniform. Queerness comes in many different bodies, colors and clothes.

Queer men are having fun taking bits and pieces of the style to make it their own. It is now a celebration of personal identity rather than conformity.

We discuss trends as temporary periods; they are often described as unsustainable and fleeting. Though, most trends have deeper implications that permanently impact how we view the world. Queer people have utilized fashion throughout history to carve out spaces for themselves where they don’t belong.

To all gay men, keep on rocking your jorts. I cannot wait for a warmer spring when I can throw on my own pair.