The Queen of the Mini

Graphic by Margeaux Rocco.

Marked by sweeping social and political change, the swinging ‘60s were a period of hope, activism, inclusivity and shifting attitudes toward fashion. Framed by the colorful rhetoric of peace and love, and fondly remembered as the age of go-go boots and lava lamps, the decade sparked hope for a more forward-thinking nation.

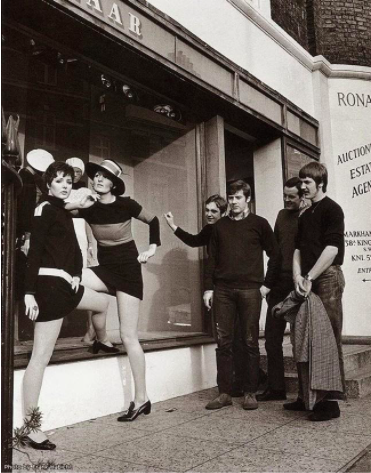

Mary Quant and models at the Quant Afoot footwear collection launch, 1967. (© PA Prints 2008)

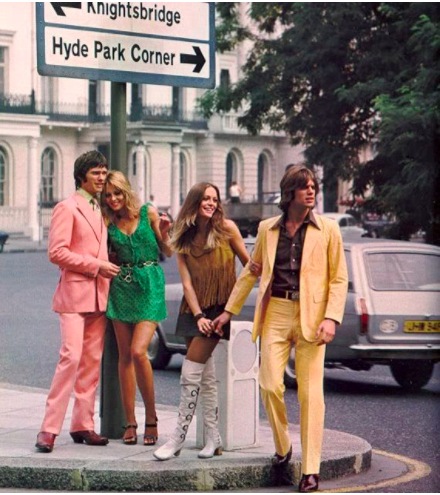

The 1960s set the scene for the ‘Youthquake,’ a new domination of youth culture that saw designers respond with a much more liberal, daring approach to fashion. Boasting exuberant colors and fresh trends, designs in the youthquake rejected the conventions and niceties of traditional fashion norms, of what could be worn when and by whom.

November 1965: Chelsea fashion designer and make-up manufacturer Mary Quant. (Keystone/Getty Images)

Mary Quant was an instrumental designer of this rebellious era. A born-and-bred Londoner, Quant studied illustration at Goldsmiths College following her parents’ refusal to let her apply to a fashion course. Despite their disapproval, in 1955, Quant opened up her first boutique shop on the King’s Road in London: Bazaar. The area of her store was populated by the ‘Chelsea Set,’ a group of young artists, contemporary socialites and film directors who were interested in exploring new ways of living, dressing and behaving.

Quant’s main aim with her boutique was to make her clothes affordable and accessible to the youth. She set a new tone for the fashion industry by encouraging young people to dress to please themselves and to treat fashion as a ‘game’ [McKinnell, Joyce (1964), Beauty, Harper Collins]. After becoming frustrated with the limited range of garments offered on the wholesale market, she decided to stock her shop up with clothing she had designed herself. Knee-high, patent, lace-up boots and bold and boisterous ribbed jumpers were the result and eventually came to epitomise the ‘London Look.’

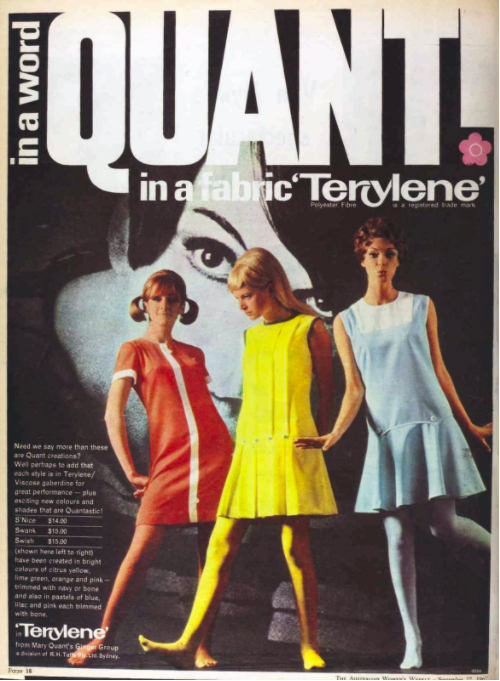

LEFT: Rave Magazine, 1966; RIGHT: Twiggy in Mary Quant, 1960s

Entrance into Quant’s Bazaar was no ordinary experience. Loud music, eye-catching windows and free drinks turned shopping into less of an errand and more of a hobby. The scene that Quant created was substantially different to the courtiers, department stores and chains that reigned the mainstream London fashion market. Young women traveled across the city to the enchanting yet informal environment of Bazaar and stayed late into the evening in search of the ‘radically different’ that Quant seemed to provide.

The mid-1960s saw Quant at the height of her fame with the introduction of the miniskirt. Young girls flocked to her stores and queued up along Kings Road, desperate to get their hands on Quant’s new designs. “It was the girls on the King’s Road who invented the mini ... we would make them the length the customer wanted. I wore them very short and the customers would say ‘shorter, shorter!’” Quant once recalled. She is also often credited with the invention of colored and patterned tights and hotpants which later grew to become British fashion staples.

Not only did Quant play a critical role in the transition of trends, but she also had a large impact on the women’s rights movement. In the ‘60s, the world of British women was limited in almost every respect from the way they dressed to the occupations they undertook. Most women were expected to follow one path — marry in their 20s, start a family early and devote the rest of their life to homemaking.

Image via Pinterest.

However, inevitably, there came a point where the frustration and outrage expressed by women could no longer be ignored and the people of Britain grudgingly gave in and accepted the basic tenets of the ‘60s feminists. In addition to the introduction of laws, there was also a huge advance in female expression, and the manner in which women were expected to behave and dress was challenged.

Quant’s mini skirt was arguably the trigger of this fashion revolution. The appeal of her miniskirt was that it was youthful, stylish and liberating. The mini was worn by feminist frontrunners Germaine Greer and Gloria Steinhem who embraced Quant’s designs as symbols of changing times. The raised hemline and exposed upper thigh acted as a political statement and marked a new sexual reclamation. It gave women a way to move past their traditional roles as housewife or mother and enabled them to create their own identities.

The strict cinched waist corsets and preppy skirts were left in the ‘50s; shift dresses, hot pants and short skirts that allowed a woman’s legs to be free so she could dance, run and do whatever she pleased.

Quant’s look encapsulated the spirit of the British feminist movement —brave, bold, new and fun — and her simple yet rebellious designs put out a youthful and energetic look that personified the rebelliousness of the swinging ‘60s. Quant didn’t realize it at the time, but her fashion statement set a lifelong precedent for how women would dress themselves in the future.