Tradition to Trend: The Chicago Blackhawks and Native Imagery

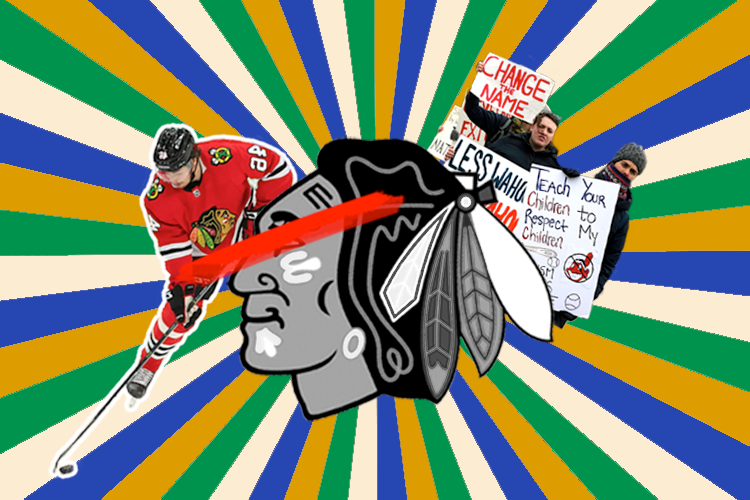

Graphic by Ashley Xu. Images via Wikipedia, the New York Times and CBS.

Forget New York Fashion Week and its haughty couture: the real finger on the pulse of fashion is not on the runway, but on the field. . . and on the ice and in the dugout.

Laced with tradition, patriotism and good ol’ fashioned family values, sports jerseys probably won’t win any style awards any time soon, but they are a good indicator of how average America, outside of the bubble of elite fashion, feels about what is and is not appropriate to wear.

Exactly for this reason, Native imagery and tribal identifiers on team merchandise are at the center of the sports fashion (what a fun oxymoron!) debate, with fans and owners arguing over whether or not donning a Native American caricature and rooting for the “Chiefs” is disrespectful.

For many teams, this summer was a reckoning. After blatantly silencing Colin Kaepernick following his protests of the National Anthem, the NFL did a 180, issuing an apology to the former quarterback — though not re-hiring him — and condemning racism and systemic oppression in all forms. In July, Washington D.C.’s football team followed up on this statement and announced that it would change its name and logo to the cleverly chosen “Washington Football Team.” The Cleveland Indians followed suit, announcing that they, too, will be changing their name after the 2021 season.

Chicago Blackhawks fans celebrate their team in Blackhawks’ gear. Image courtesy of the Blackhawks.

In home sweet Chicago, a different story unfolds. In December, the Chicago Blackhawks, the city’s professional ice hockey team, reaffirmed their commitment to their team’s title and logo, citing deep partnerships with the Native American community and their work to preserve Sauk tribe leader Black Hawk’s history.

Joseph Podlasek, member of LCO Ojibwe Tribe and founder and CEO of the Trickster Cultural Center, a partner of the Blackhawks, says his organization does not see a need for a logo change. Though Podlasek concedes that Washington’s mascot “had to go,” he tells STITCH that the Blackhawks’ logo is different because it is representative of a historical figure instead of being a Native mock-up. More importantly, he says, the Blackhawks were receptive to a relationship with the cultural center and gave it a platform at games and on their website to share Native culture.

Podlasek hasn’t always been a fan of the Blackhawks. 10 years ago, he was turned off by the 300 or so fans at every game sporting headdresses and warpaint in the stands. Headdresses are sacred in his community, he says, and being given the honor of wearing one has to be earned by an individual over a long period of time. Applying face paint for games is also inappropriate, as it’s reserved for times of war, he explains. Podlasek is proud that since the cultural center began its work with the Blackhawks, however, the team has banned headdresses at games all together.

Slowly, Podlasek and Rocky Wirtz, the owner of the Blackhawks, have begun to build trust between the organizations.

“When we first met with the Hawks, we said, ‘This is going to be a long-term relationship.’ You can't flip me a couple million dollars and say, ‘Oh, we did our thing and we're done.’ We're not looking for that. I wanted a long-term relationship that's going to culturally educate them, the fans, and hopefully build a bridge with our community,” Podlasek explains.

The Eagle Staff at a Blackhawks game. Image courtesy of The Trickster Cultural Center.

It’s this opportunity for education that makes the partnership so beneficial for the Trickster Cultural Center. For 10 years, Podlasek says the Blackhawks have granted the organization space to bring its community’s veterans and elders onto the ice to be celebrated. More recently, the cultural center has begun bringing the Eagle Staff, the first flag of the nation “long before Betsy Ross,” onto the ice. Podlasek says these initiatives are important for sharing their history and moving the Native narrative away from the Cowboys and Indians trope overplayed in Hollywood.

Without the Blackhawks, Podlasek points out, the cultural center wouldn’t have access to a fan base of over a million people in which to post videos of Jingle Dress dances or showcase Native artists. “If you take everything Native away, where's the opportunity to open that door for education?” he asks.

Not all Native organizations in Chicago agree with Podlasek’s take on the Blackhawks, however. STITCH reached out to several Native cultural organizations in Chicago, but none responded to requests for comment. However, the American Indian Center of Chicago, which had previously partnered with the Blackhawks, released a statement in 2019 announcing an end to their partnership with the team because of the perpetuation of “harmful stereotypes.”

“This is simply window dressing and a diversion from their racist mascot. If they were truly serious about honoring Native people, they would change their mascot,” Les Begay, a member of the Diné Nation and board member of the American Indian Center of Chicago, said to Native News Online in November.

The National Congress of American Indians has also stayed firm in their stance against “Indian” sports mascots since the 1960s, citing psychological and cultural harm, especially amongst Native youth.

It’s a much easier discussion when looking at Gucci’s blackface sweater or Marc Jacobs putting white models in dreadlocks to point to cultural appropriation and blatant ignorance. But when decades of tradition and hometown pride are mixed in, the already muddy waters turn muddier.

The intricacies of wearing a representation of another person, especially a person of a marginalized community, dig deep into questions of what is historical celebration and what is instead trivializing a community. Of course, only Native people can answer these questions, but often even then, the question turns toward if they can use their appropriation for their own gain, not necessarily how they feel about the use of Native-associated imagery and practices itself.

For Podlasek, disregarding logo concerns in favor of working towards the larger picture of education of, and respect for, Native culture is necessary. For others like the AIC, the use of Native imagery without Native consent is disrespectful in and of itself.

They agree, however, that there is power in fashion as a cultural unifier. A headdress and war paint aren’t a decorative piece to top off a perfect game day outfit, and to wear one without the knowledge and respect for the accompanying customs is where these organizations point to harm. Fashion is and should be a space of creative freedom and expression, but that freedom can’t come at the expense of the dissociation of a piece with its original culture.

Though the Blackhawks may not be changing their logo any time soon, fans still have the autonomy to choose how (or if) they celebrate our city’s ice hockey team. Whether appropriate or not, it is up to you, the wearer, to decide if the Blackhawks are sustaining culture or stealing it, and if you, by extension, are doing the same.